Impeachment: Derrotados Pela Lei

A Summary in English

I began my book in March of 2016, a few days before the largest protest in the history of Brazil. The impeachment of Dilma Rousseff was uncertain at the time, yet I felt that history was being written – and that I, too, should be writing that story.

Most events were captured as they occurred, so that I could incorporate details that would otherwise get lost over time. In fact, my initial idea was to keep a diary. It took me more than one year to finish it and several months to edit it. “Impeachment: Derrotados Pela Lei” (or “Impeachment: Defeated by the Law,” in English) was published right after I went to Princeton. I’m planning on hosting an event to officially release it as soon as social distancing protocols amid the COVID-19 pandemic ease.

One day I intend to have all of its 234 pages translated into English. Until then, I invite you to read the following summary of my book. I also included pictures and a few useful links to make you more acquainted with Brazilian politics.

Impeachment: Defeated by The Law

“Verba volant, scripta manent (Spoken words fly away, written words remain).”

With this Latin proverb, Michel Temer started a letter to Dilma Rousseff, still president at the time. After their leakage, these words would set the tone of yet another political crisis, increasingly fierce, between the nation’s highest officials.

On that day, December 7th, 2015, one could not foresee that the VP’s letter would contribute to his partisans clash with the administration, to Rousseff’s impeachment, and to his ascension to the presidency.

Nor could one anticipate that the unfolding of the Car Wash Operation, unpretentious in the first half of 2014, would reach the upper echelons of government – punishing criminals that were involved in the world’s largest corruption scandal.

Politics would never be the same. Brazil, much less.

Since the events I witnessed can only be perpetuated if put on record, I decided to write this book. After all, verba volant, scripta manent.

To meet this challenge, I interviewed key activists, conducted research, and followed events closely. Hence, in certain sections, I exposed my eye-witness accounts. In others, establishing an appropriate distance, I promoted a rigorous and, to the best of my ability, unbiased scrutiny to turn these pages into a scholarly work. In summary, I focused on being fair with the individuals who were mentioned, with my conscience and, most importantly, with history.

Dilma Rousseff and Michel Temer, tied together by 54 million votes in the 2014 elections. Photo: Pedro Ladeira/Folhapress.

Antecedents

The book begins with the analysis of two drivers of the pro-impeachment movements.

1) To generate an understanding of how to protest, acquired in two moments.

Firstly, demonstrations for the ouster of President Fernando Collor showed activists the importance of popular mobilization. Civic movements, congressmen, and the press had to be engaged for Congress to approve the impeachment. Additionally, the impeachment’s legal processing (filing of charges, Special Committees, hearing of witnesses, votes by a qualified majority, appeals filed at the Supreme Court) taught the Brazilian people how intrinsically democratic this constitutional remedy is.

Therefore, I analyzed events from 1992, when Collor was impeached, with focus on their unfoldings in 2016.

Secondly, demonstrations in June of 2013, organized by the Free Fare Movement, motivated even larger protests. These were notable for not having clear leadership and for prohibiting political propaganda, a stance equally present in the protests for the impeachment of Dilma Rousseff.

2) To worsen the dissatisfaction of the population with both the Rousseff administration and the president’s political party, the Workers’ Party (PT).

In 2006, by the end of President Lula’s first term, a congressional vote-buying scandal was revealed – Mensalão, at the time the largest corruption scandal in the history of Brazil.

Despite the crisis that was installed, Lula got reelected later that year. In 2010, he finished his second term with overwhelming popularity and elected his successor, Dilma Rousseff.

In August of 2012, the “Mensalão” trial began and received ample coverage from the press. With the imprisonment of several upper-echelon politicians, there was hope that impunity would come to an end. Yes, Brazil could change. And the strengthening of the Brazilian institutions, such as Federal Police, Public Ministry, and Justice, through the support of public opinion and popular demonstrations, would be a means to make it happen.

Ultimately, in 2014, Dilma Rousseff was reelected at the expense of her own legacy – jeopardized by the worst economic crisis in the recent history of Brazil and by the worst approval rating registered thus far. Ms. Rousseff was reproved by 71% of the population – while Fernando Collor, right before his impeachment, was reproved by 68%.

The first protest in Manaus, on November 1st, 2014, assembled less than 50 people. As usual, I was carrying my Brazilian flag and a speaker (I am the third protester from left to right). I was 17 years old at the time.

Protests Begin

In October, Alberto Youssef confessed that Rousseff and Lula knew of embezzlement cases in the state-owned Petrobras. This fueled the first demonstrations, organized on November 1st and 15th, 2014. Protesters aimed to support the Car Wash Operation and to fight corruption, whereas only portions of protesters advocated for the impeachment.

The year 2015 was a turning point for the opposition. In February, an anonymous message inviting the population for a peaceful protest on March 15th went viral. Making use of this opportunity, some groups reinforced the invitation.

Seven days away from the demonstration, Ms. Rousseff addressed the nation. The Movements, in response, organized a cacerolazo to call for attention, joined by thousands of Brazilians around the country. The protest was covered by major TV newscasts and set the tone for the upcoming demonstration.

On March 15th, Brazil witnessed one of the largest protests in its history. In São Paulo alone, according to the city’s Police Department, more than one million protesters gathered on Paulista Avenue. Due to this unprecedented event, the realization of the impeachment’s feasibility had finally been born. To that end, however, Congress had to heed the claims that were coming from the streets.

On March 15th, we organized a protest with more than 30 thousand people in Manaus. It was the first time that I spoke to a large audience. I remember the thrill until this day.

Making It Happen

One of the key concerns faced after the protest was how to keep pressuring Congress and how to maintain the impeachment’s relevance in society. To some, the answer was to organize yet another large demonstration.

Thus, using the motto “The Next One Will be Larger” and less than one month away, the organizers committed a dire mistake. The low engagement on social media and in the press worked as a gauge of the upcoming event, which would attract less than half the number of protesters of March 15th. These numbers, although superior to the protests of 2014, were a major red flag. Some started to doubt that the impeachment was still supported by the majority of the population. The administration, in turn, was relieved.

This statistic merely reflected erroneous decisions made by activists and the lack of breaking news days on the eve of the demonstration. Evidencing the continuous national support of the impeachment, a poll released by the Datafolha Institute on April 11th showed that 63% of Brazilians supported Ms. Rousseff’s ouster (similarly, the previous showed 68% of support on March 19th).

Still, the April 12th protest was an important lesson. Henceforth, activists would no longer be attached to large demonstrations, preferring smaller rallies instead. The clearest example of this new mindset was the “March for Liberty,” organized by the Free Brazil Movement in the same month. Aiming to file charges for the impeachment, they traveled from São Paulo to Brasília on foot, in an adventure that lasted from April 24th to May 27th.

A picture of when I met Rogério Chequer and other Vem Pra Rua activists. At the time, I was traveling to Brasília to help articulate the impeachment in Congress. As a result of my networking, I joined the movement as their leader in Amazonas.

In June, Vem Pra Rua and other movements announced that the third protest would be held on August 16th. With two months for publicity at hand, the rally received reasonable press coverage and social media support. In turn, they lacked a piece of shattering news that could potentialize the population’s unrest, such as the leakage of a plea bargain’s content or the arrest of a politician. This resulted in a demonstration smaller than March 15th but much more impactful than the one from April 12th.

Miguel Reale Júnior, Hélio Bicudo, and Janaína Paschoal filed a petition for Dilma Rousseff’s impeachment on September 1st. Additional charges were attached on October 21st to include the so-called “fiscal pedaling” – the use of payments made by state-owned banks to hide the government’s deficit. Smaller protests continued around the country and, on October 7th, the Federal Court of Accounts issued a recommendation for the reproval of Ms. Rousseff’s 2014 accounts, which have not occurred since 1937.

On the impeachment front, several Movements set camping in front of the National Congress on October 21st. To the same end, a group of activists from the movement NasRuas handcuffed themselves around a pillar inside the Green Hall of the Chamber of Deputies.

The speaker of the House accepted the petition on December 3rd – which we celebrated with a protest ten days after it (you can watch my speech here). Later that day, the Movements announced a new demonstration for March 13th, 2016.

In November of 2015, I was promoted to the position of spokesperson of Vem Pra Rua. My first task was to join the camping on the Congress’ lawn. One of my life’s greatest adventures.

A Historical Day

However, we suffered a setback in December. After a controversial meeting, the Supreme Court decided to alter the impeachment procedure – attributing to the Senate the prerogative of, by a simple majority, decide not to admit the trial against the president, despite a potential decision by a qualified majority at the Chamber of Deputies. 2015 ended on a low note, intensifying the challenges that we had to face.

The fear that vacations could cool down the impeachment came to an end as soon as bad economic data and new phases of the Car Wash Operation came into play in early 2016.

Just a few days before the fourth protest, two breaking news shattered the nation and, as a result, increased the protest’s relevance. The first, on March 3rd, was the release of Senator Delcídio do Amaral’s plea bargain by the news magazine IstoÉ. He was no ordinary senator – but the former Senate Majority Whip and a member of the Workers’ Party (that is, Lula and Dilma Rousseff’s political party, known by its initials in Portuguese, PT).

To the Federal Police, the Brazilian equivalent for the FBI, Mr. do Amaral stated that Ms. Rousseff had tried to interfere in federal investigations and that Lula had ordered the bribing of key figures in the Mensalão and Petrobras scandals.

The second breaking news occurred on the following day, March 4th, with the Car Wash Operation’s 24th phase. Searches were conducted at the residences of former President Lula and his son, Fabio Luiz. On the occasion, the federal judge Sérgio Moro also authorized Lula’s “coercive testimony” (in Portuguese, “condução coercitiva”).

These occurrences created the most favorable atmosphere for the demonstrations, instantly reflected on social media. Vem Pra Rua’s event on Facebook, for instance, had more than 7 million invitations. At that point, we already knew that the Sunday protests would be historical.

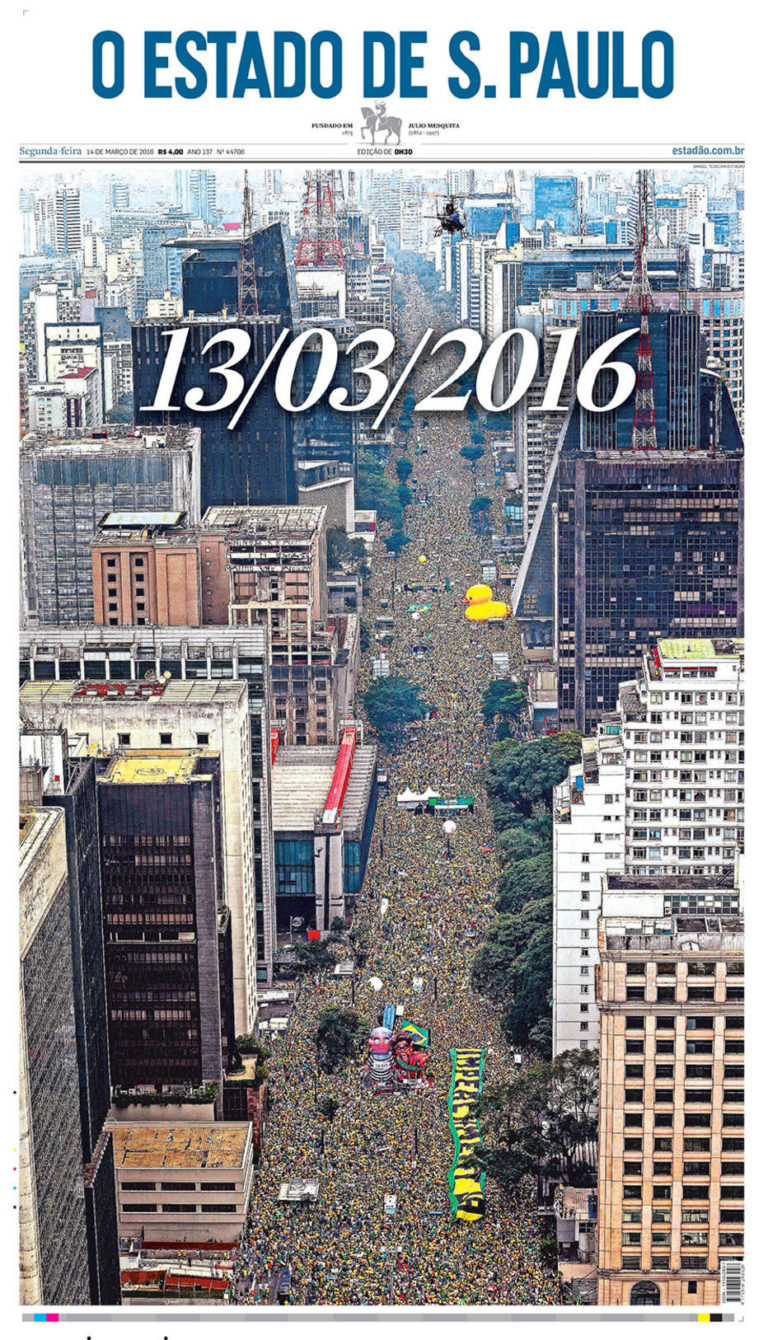

On March 13th, our expectations got beaten by reality. At least 6 million people occupied the streets of Brazil to demand the impeachment of Dilma Rousseff. “Anti-Dilma protest is the largest in history,” the newspaper Folha de S. Paulo highlighted on the following day. O Estado de S. Paulo, in turn, solely displayed the historical date on the cover of its March 14th issue – and nothing more.

Cover of the newspaper O Estado de S. Paulo on March 14th, one day after the largest protest in the history of Brazil. Indeed, a picture is worth a thousand words.

"Yes, for the future!"

As the impeachment petition gained traction, the frontline shifted from the streets to the halls of Congress. Constituents and activists would be left with digital-activism tools to pressure their representatives. To that end, Vem Pra Rua developed the platform “Impeachment Map,” which facilitated the messaging of representatives on different media, as well as the accounting of favorable, contrary, and undecided voters.

Similarly, multiple newspapers and magazines released their scores. The most notable, O Estado de S. Paulo’s “Impeachment Score,” was daily updated and displayed on the cover of printed and digital issues. On April 14th, the newspaper registered that the necessary 342 congressmen, two-thirds of the House, were openly in favor of the president’s conviction.

As a result of months of scrutiny at Special Committees, the Chamber of Deputies analyzed the charges on April 17th with a roll call vote.

At 11:05 pm, Congressman Bruno Araújo registered the 342nd vote: “Yes, for the future!” he cried. Overall, there were 367 “Yes,” 137 “No,” 7 abstentions, and 2 absentees.

The first challenge had been overcome as a result of two years of persistence. From that moment on, regarding the procedure established by the Supreme Court in December of 2015, the senators would have to decide whether to start the trial – suspending the president from her office – and whether to impeach her – which required a vote by qualified majority (54 of the Senate’s 81 members, the highest quorum in the Brazilian Constitution).

On April 17th, 2016, I spoke to a crowd of protesters that gathered in front of Congress in Brasilia. A few hours later, the Chamber of Deputies authorized the admissibility of the impeachment trial.

The Trial

For the last part of my book, I detailed the trial in the Senate. This includes the vote for the petition’s admission (the Chamber of Deputies only authorized such admissibility), hearings, and the final judgment – all of which were conducted by the senators, judges in this trial, and the Supreme Court’s chief justice, who presided most sessions. To that end, I explored a wide range of documents, testimonies, and reports.

On March 12th, the Senate approved the Impeachment Special Committee’s report in favor of the petition. The score evidenced the astonishing support that the impeachment received in the Upper House of Congress, with 55 “Yes” and 22 “No.” On the same day, Michel Temer took office as interim president.

The judgment, presided over by Chief Justice Ricardo Lewandowski, started on August 25th and had its climax with Rousseff’s speech at the tribune. On the occasion, the defendant faced all 81 senators, judges of that trial, to answer intricate questions.

On August 31st, 61 senators found Dilma Rousseff guilty of violating article 85, items V (probity in the administration) and VI (budgetary laws), of the Brazilian Constitution. The impeachment had finally been approved.